Radiating Biographies in Postcard Forms: Ursus, on the Earth and in the Sky

By Nicola Levell (University of British Columbia)

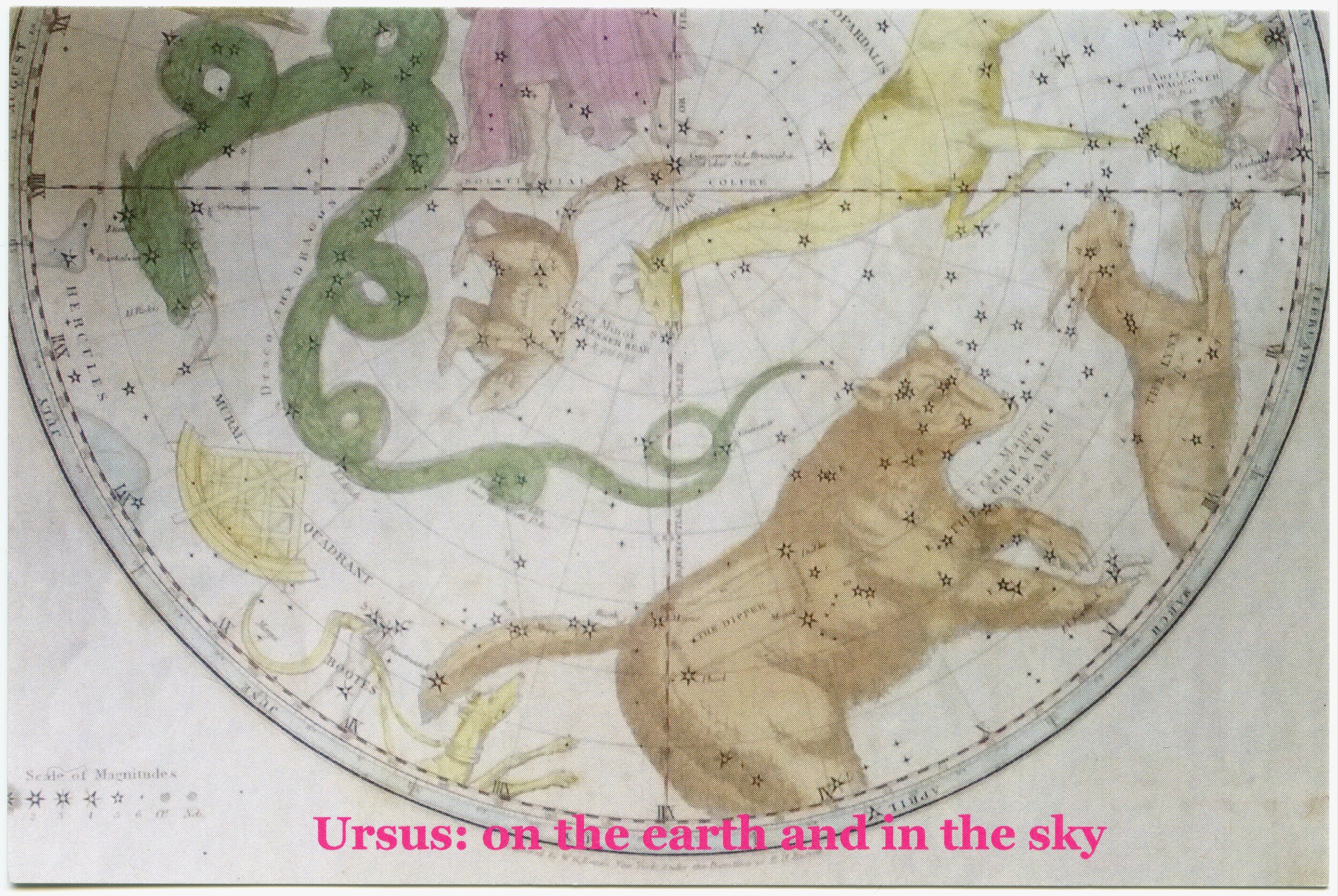

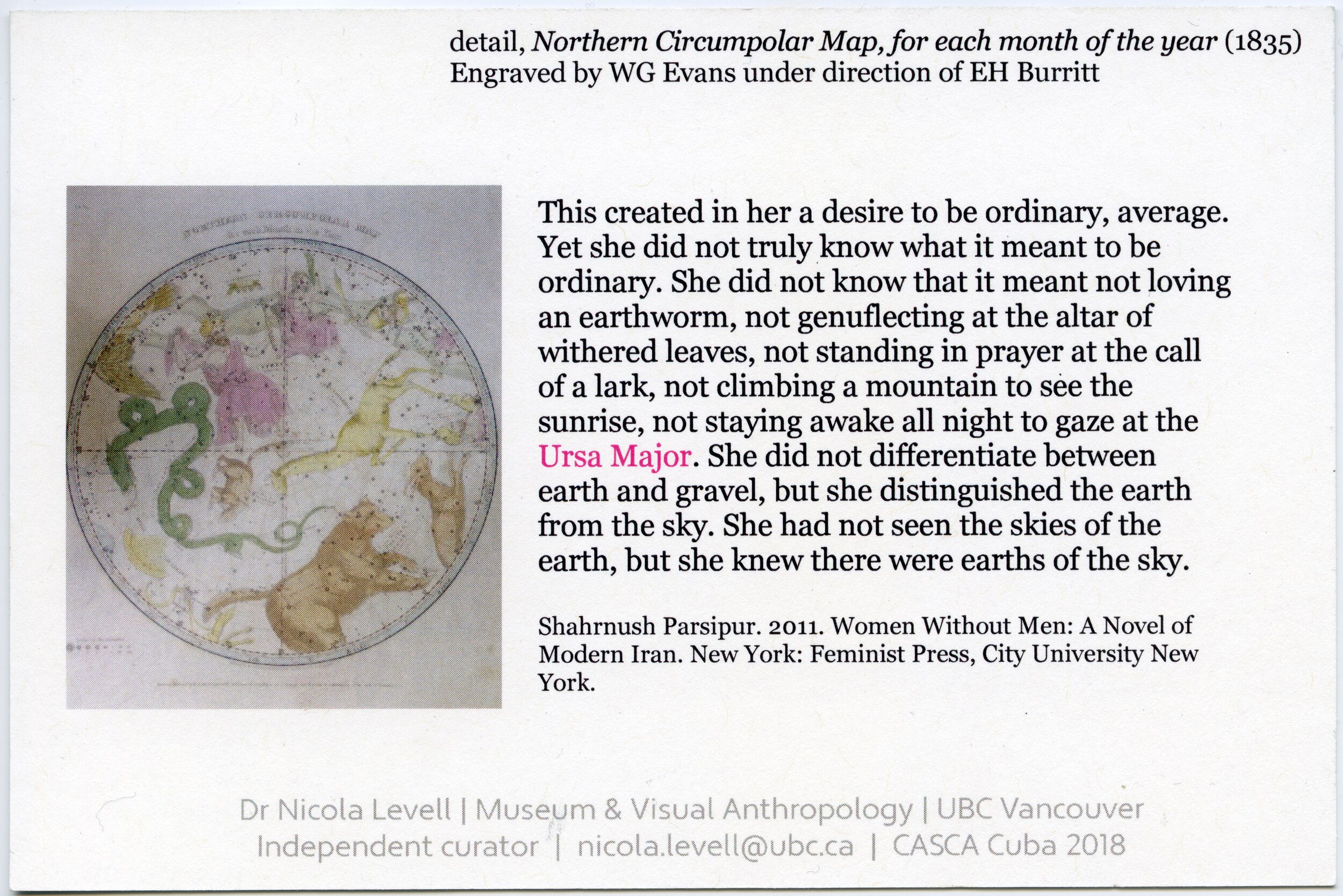

The above is a postcard, front and verso—please look at the images and read the text. It is drawn from a set of six postcards entitled Ursus: On the Earth and in the Sky, which I made to illustrate a paper that I gave at the Canadian Anthropology Society (CASCA) conference in Cuba in 2018. My paper was part of a series of roundtables, workshops, installations, and film screenings, "Moving Towards Ethnographic Hallucinations," organized by the Centre for Imaginative Ethnography. Held in the atmospheric Casa Dranguet, in the historic heart of Santiago de Cuba, the series brought together anthropologists, artists, and other practitioners to "engage in lively encounters and fruitful debates about arts-based practices, creative methodologies, and productive collaborations." My presentation was enfolded in a panel, "Biographical Experiments," to invoke the words of the organizers Denielle Elliott and Leslie Robertson:

Papers in this session address ways that variously known lives come into being through purposeful acts of performance, story-telling, inscribing, and imagining. We come together with questions about the possibilities that biography carries for particular narrators and their documenters; for the performers of fantastic selves; or, the intangible subjectivities of other-than-human being.

Biographies, for me—someone steeped in museum anthropology and material culture studies for over two decades—conjure the concept of the life histories of objects, as detailed in Appadurai's classic volume The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (1986). In this seminal work, Appadurai and his contributors explore the untapped terrain of the social lives of "objects," or what one of the authors, Igor Kopytoff (1986, 64), more pertinently terms "the cultural biographies of things." This volume was part of the incipient shift in anthropology's epistemological matrix, in its new materialist desire to extend agency to nonhuman actors, or, to use Latour's network term, "actants."

While this idea of the biography of things still has abundant currency, I knew I was not interested in pursuing this exact line of inquiry again. Something else had aroused my curiosity and was gnawing at my thinking: it was the philosophical ideations threaded through the sketchbook of the visual artist and activist George Rammell that spoke of the interconnectivity or entanglement of substances, species, and things on the earth and in the sky, across time and space, and their multiple ways of being or becoming in the world.

This idea of multiple biographies of the earth, the night sky, the tree, the bear, the artist, and more besides—as inscribed and imaged in Rammell's sketchbook—became charged with possibilities. My thinking at the time was being punctured by Braidotti's nuanced musings on nomadic subjects (Braidotti 2006; Levell 2013), stimulated by Bennett's Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (2010), inflected by Wohlleben's The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate (2016), illuminated by Parsipur's Women without Men: A Novel of Modern Iran (2011), and shot through with multiple associative yet disconnected trains of lightning thought, from dreaming with Bachelard to hallucinating with Taussig. But the inspiration to create postcards and explore radiating biographies came most clearly from my engagement with the large black sketchbook.

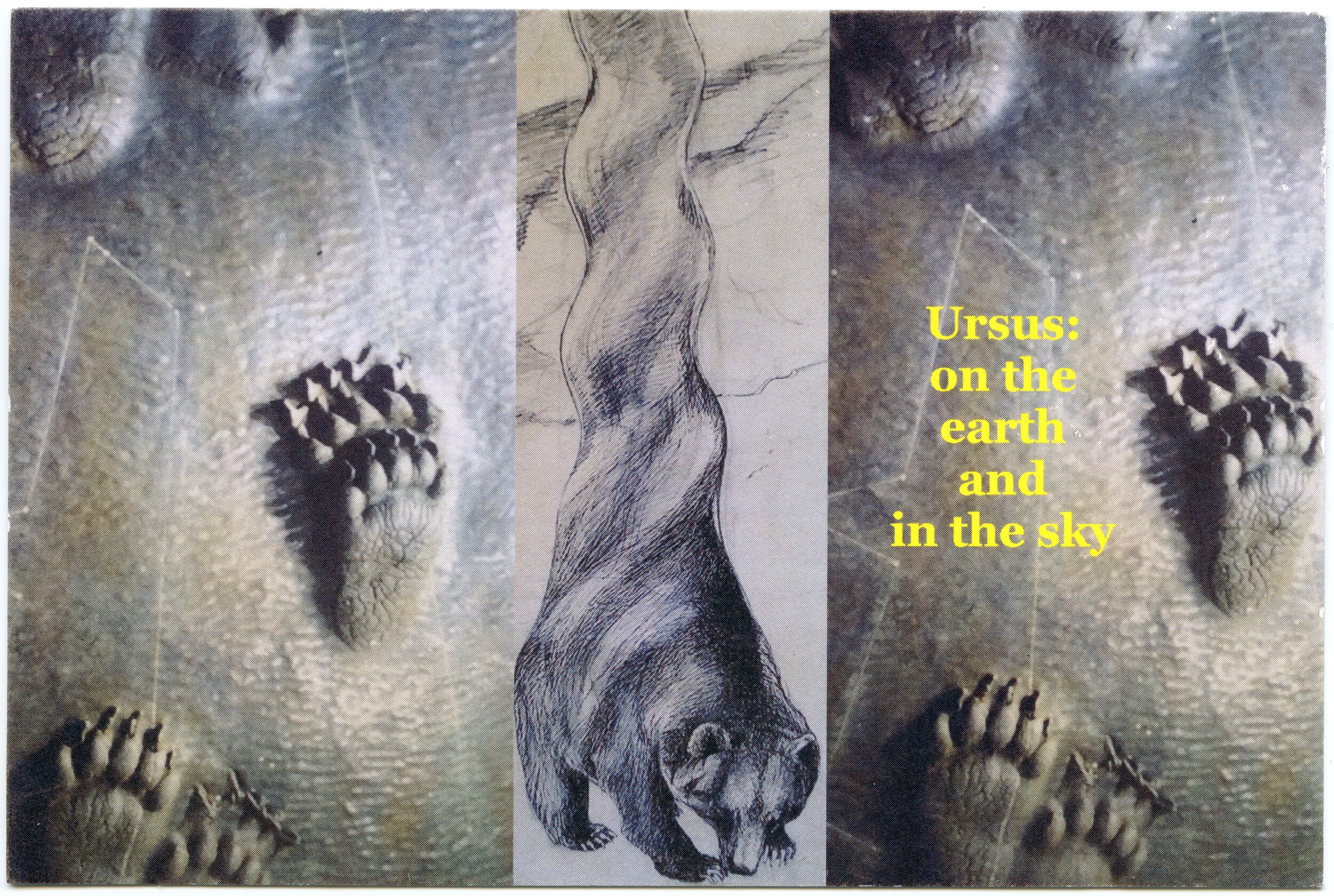

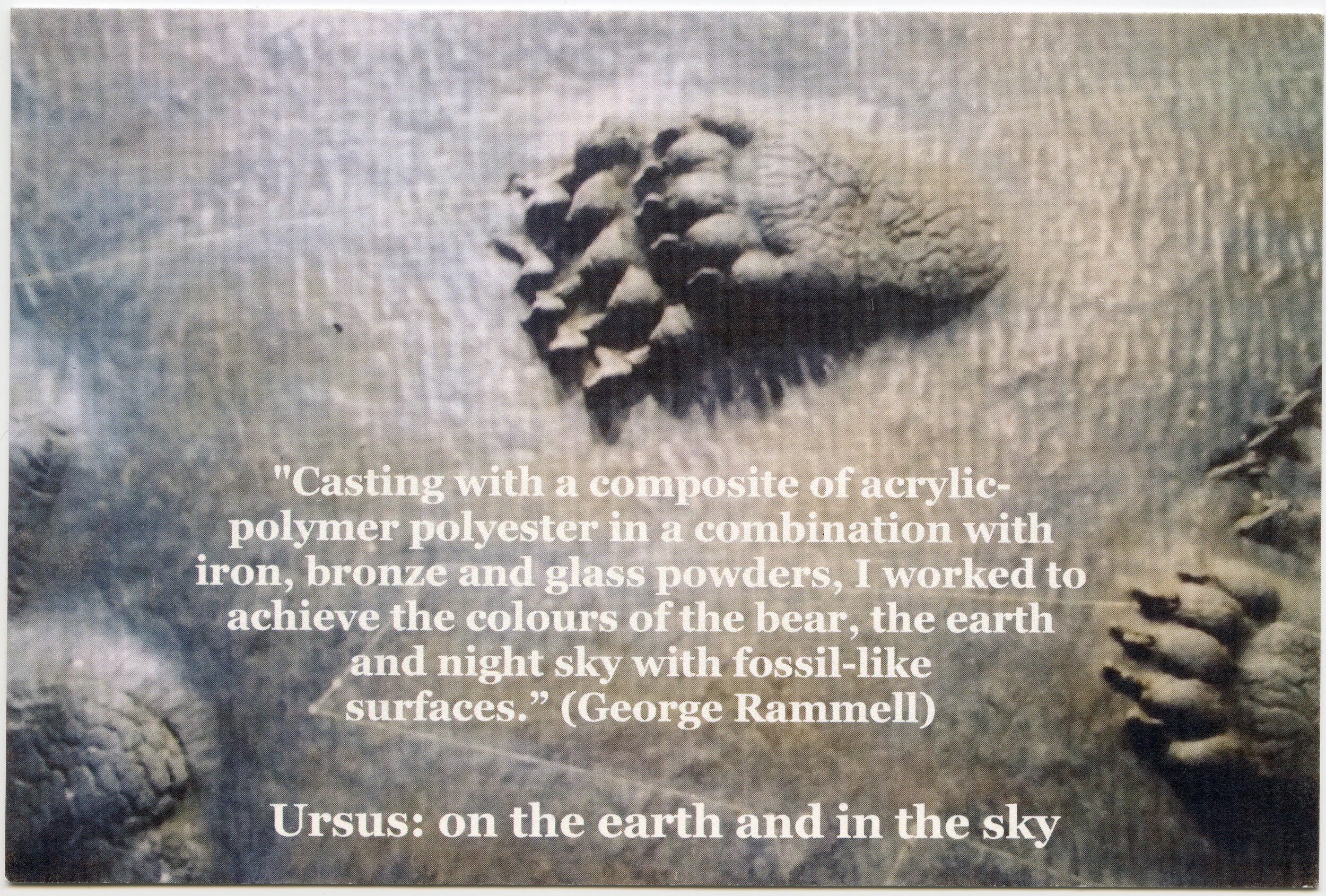

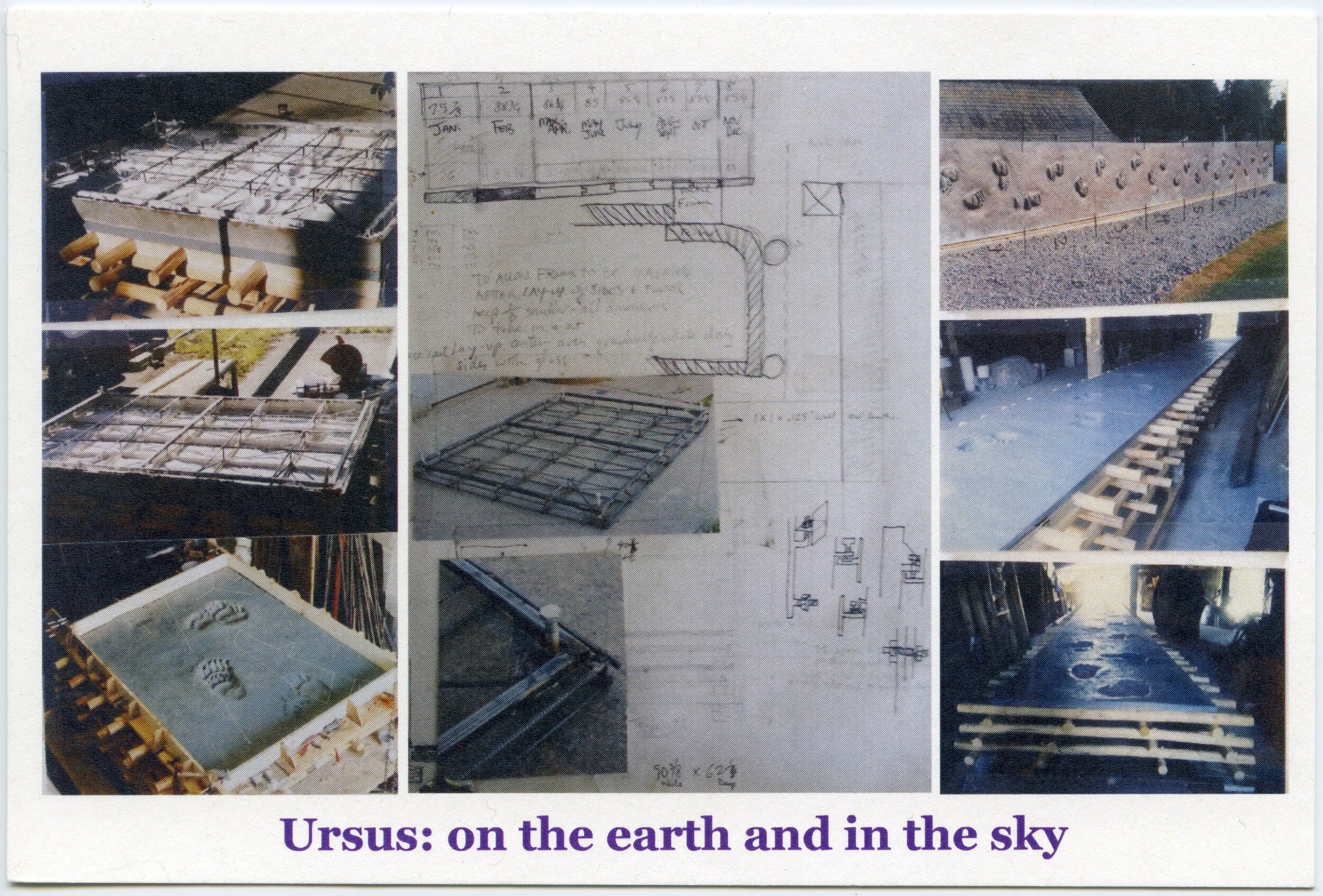

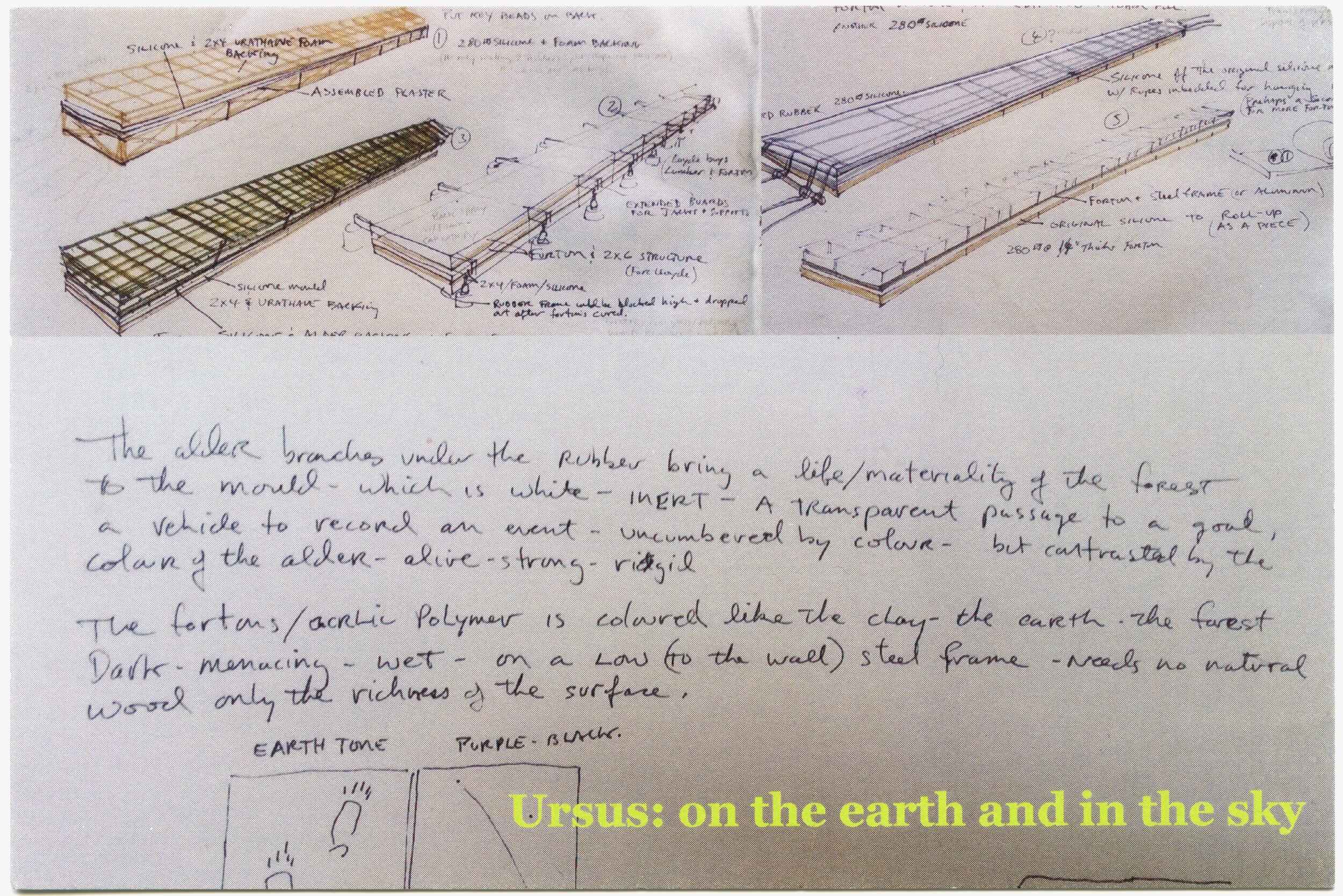

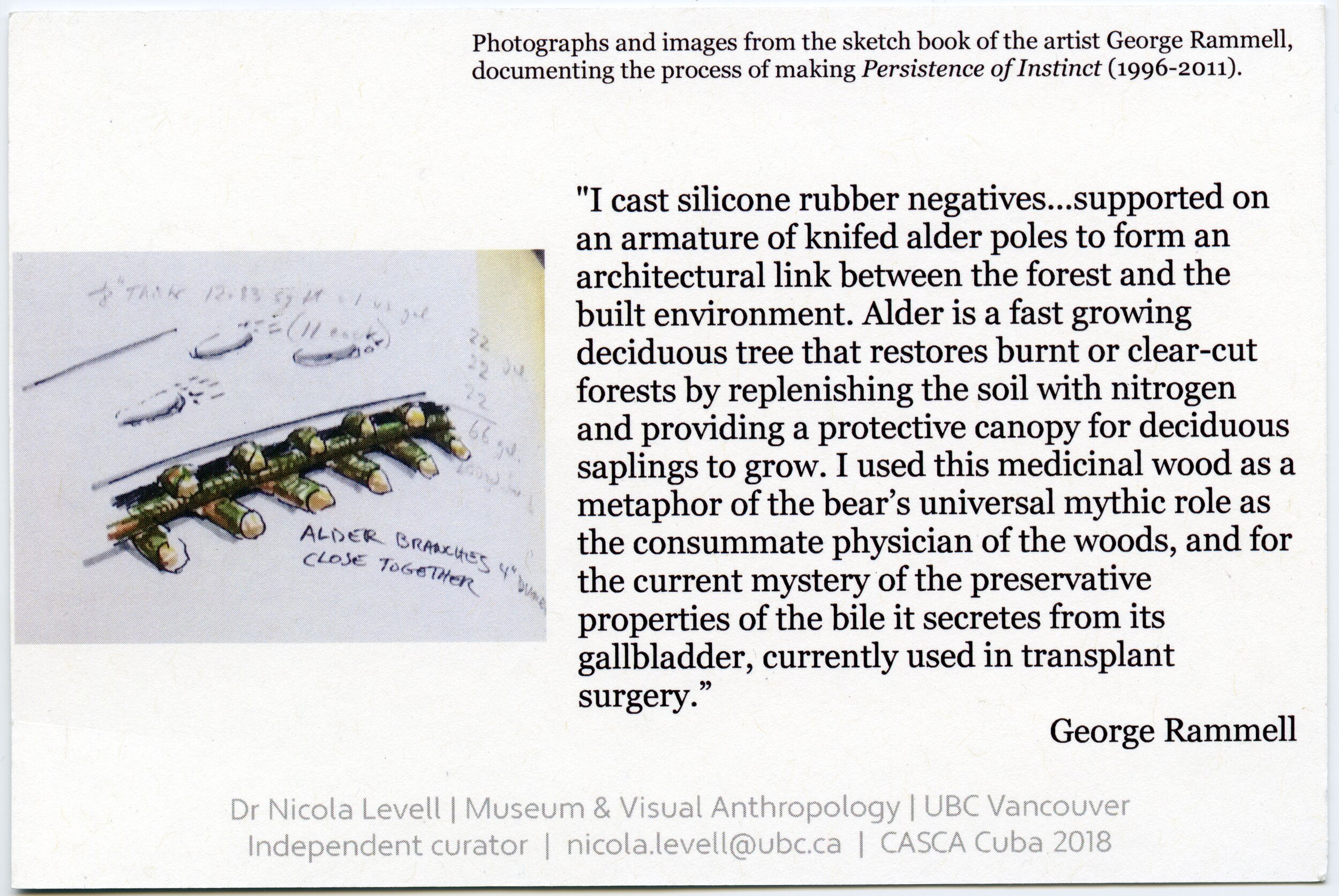

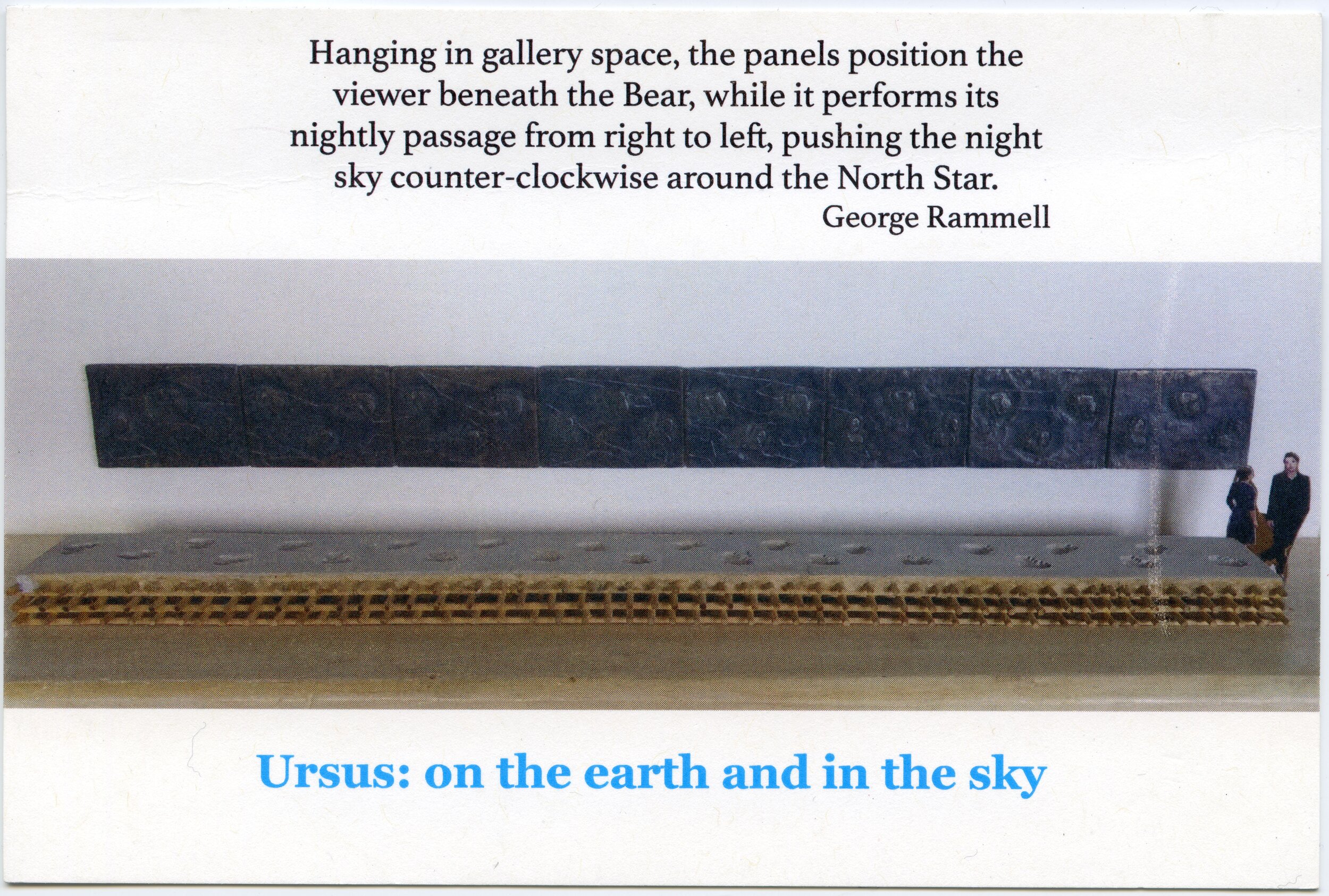

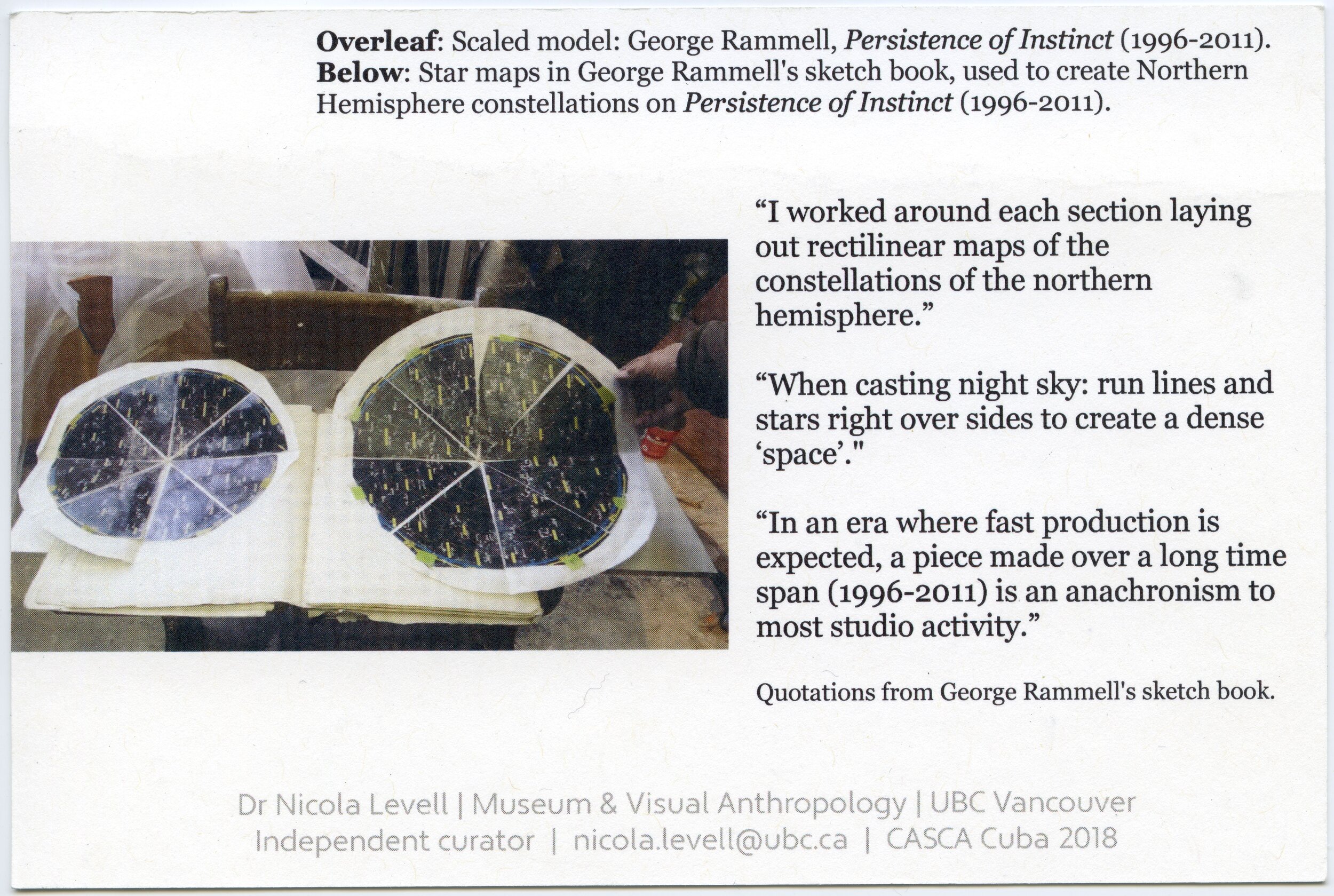

George Rammell had lent me this marvelous sketchbook for my research because it charts the fifteen-year-long process from the conceptualization to the creation of his monumental seventeen-meter-long artwork The Persistence of Instinct (1997-2011), which I wanted to include in an exhibition I was curating on the night sky. Made of clay, wood, and polymer acrylic (bronze, iron, and glass powder), the artwork consists of eight large floor panels (with bear-paw imprints or depressions) nestled in an alder-wood frame, and eight corresponding wall-mounted panels (with high-relief bear-paw molds) marked with stylized engravings of the constellations of the Northern Hemisphere. For me, the sketchbook remains an integral and inalienable part of the artwork, its making, and its presence: it is an invaluable artifact, a multisensorial delight, a worn Pandora's box full to overflowing with ideas that reveal the creative process in textual and visual forms. To see, to touch, and even to breathe in the book is to experience its life force and history. Bruised and scuffed, marked with plaster and paint, its broken spine is held together with frayed silver duct tape. Its dirtied body bulges with insertions: faded photos, old inkjet prints, scribbled ideas and recipes, scaled drawings and diagrams, a fold-out double-page spread of dissected star maps of the Northern Hemisphere, scribed memories of a Haida mentor who passed from this world to another, plus a myriad of other observations, thoughts, and things.

In preparation for the conference in Cuba, CASCA sent numerous emails containing travel tips, recommendations for eateries and accommodations, and other guidelines and advisory notes. I took special note of one: "It is likely that the university and conference sites will not have WiFi connections, please plan for offline presentation and communication. . . . Printing may be difficult to arrange, please bring hard copies of documents" (Boudreault-Fournier and Haber Guerra 2017). So, I began to think more deeply about how I might effectively communicate my research into the different material, iconographic, and affective dimensions of Rammell's monumental artwork and what alternative media and creative methods I could use to encourage collaboration and audience engagement. How could I trace and convey the intersecting biographies and multisensorial aesthetics that saturate and vibrate through the materiality of The Persistence of Instinct? I knew I wanted to do something based on the sketchbook. But how could I capture the poetics, the nonlinearity, and the excesses of this unruly archive of creativity? How could I visualize the processes, the thinking, the experimentation that took form over time, with some ideas realized in sculptural forms and others discarded but preserved on the well-thumbed pages of the sketchbook?

Postcards came to mind. I have a small collection of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century postcards that depict Victorian travel destinations and the architectures and displays of various international exhibitions. These cards are multisensorial and affective media. Through texture, scent, image, and handwritten back matter, they embody multiple associative biographies that transport and connect the viewer to different times, places, structures, people, and beings (see Gugganig and Schor 2020). They fuel the imagination with the possibilities of their future destinations (Derrida 1990).

With camera in hand and with Rammell's consent, I worked through his sketchbook, seeking out biographies hidden within. From these photographs, I created the set of six postcards. I printed fifty copies of each card, with matte finish, and bound them into sets. I sent a number to the artist, and I took the remainder (more than forty sets) with me to Cuba. At the start of the roundtable, on May 17 in Casa Dranguet, my postcard sets were distributed, one for each audience member, and I began my presentation:

Instead of a Powerpoint, I've created a set of six postcards for you to look at and keep. I will be speaking to these visual assemblages one at a time: I will pick them up and read their images and texts and I invite you to follow suit.

The title of my paper is "Ursus: On the Earth and in the Sky; or, the Optics of Radiating Biographies."

We will trace the idea of "radiating biographies" of different species, elements, or beings—the earth, the tree, the bear-as-artist, the artist-as-activist, and the night sky—as they intersect or connect through time and space. We will explore these radiating biographies through the prism of a monumental artwork, The Persistence of Instinct by George Rammell, a Vancouver-based artist and activist.

The metaphor of the artwork (or material form) as prism, I think, is useful to think through, especially when light is brought into the mix. Whereas the prism is a transparent form, when white light passes through, it is refracted and exits as a spectrum of visible colors: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet—a rainbow. Before Isaac Newton published his book on scientific experiments in 1704, entitled Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light, light was thought to be colorless or a little white: it was thought that the medium, the prism, acted magically, changing the light into rainbow form. Newton's scientific dissections effectively destroyed the magic of the rainbow, or so Keats lamented in his ode Lamia (1820): "cold philosophy" conquered "all mysteries": it unwove the rainbow and clipped the wings of angels.

Anthropology could be accused of similar actions: it is apprehended in some quarters as a cold discipline. Yet there are multiple undercurrents, in both theory and practice, seeking to infuse poetry, creativity, and enchantment into the skeins of anthropology. Recently, Michael Taussig, in his seductive literary and metaphysical musings, has propelled our understanding of color as an inherently unstable cultural and historical form. He pushes color beyond the concrete and physical, showing that it pervades dematerialized states that are magically interlaced with our experiences and perceptions of being in the world. In reference to paintings, Taussig (2006, 47) observes:

In other words, when we see a color we are actually seeing a play with light in, through, and on a body—refracting, reflecting, and absorbing light—something we are aware of but rarely [see] such as sunlight filtering through a forest . . . or rainbows on oil slicks on a wet roadway. Given the play with light brought about by texture, it is no wonder that color can seem to be what I call a polymorphous magical substance, twisting itself as if alive through the branches along with the dying sun.

As we know, white light transforms as it passes through a prism because light changes speed as it moves from or through one medium to another. With the artwork-as-prism, multiple biographies travel through, refracting, inflecting, and multiplying, changing direction and pace. There is a poetic fluidity or mutability to these radiating biographies as their energy paths and waves intersect and disperse, and travel on, encountering other prismatic forms.

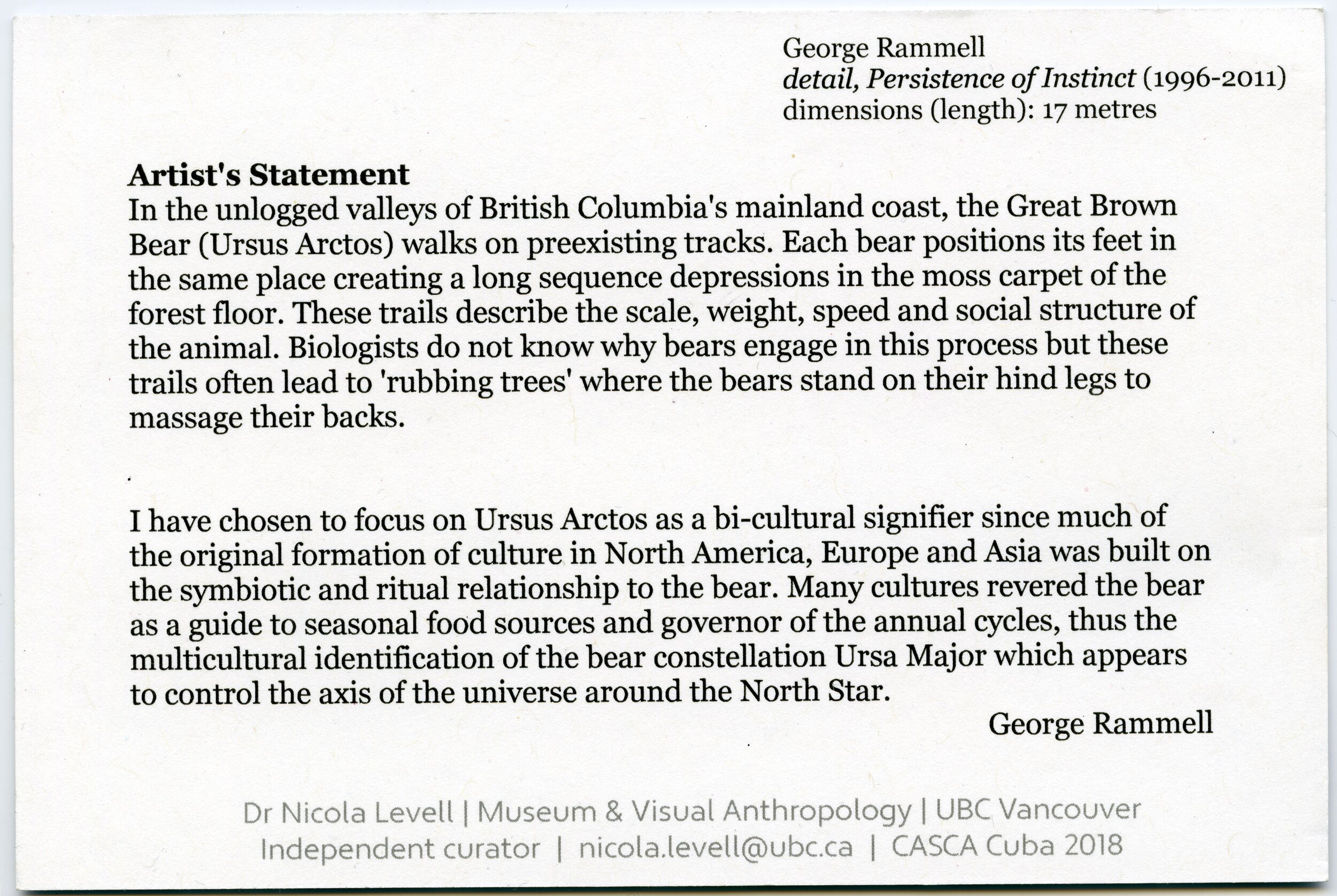

In his artist's statement, Rammell explains the textures, inspirations, and thoughts informing the prismatic artwork:

In Rammell's work, the bear is not only identified as a ritual and symbiotic companion, an earthly guide and celestial force (the constellation Ursa Major), but also as an artist. As Rammell notes, as soon as the bear started walking across the clay, the bear was becoming artist.

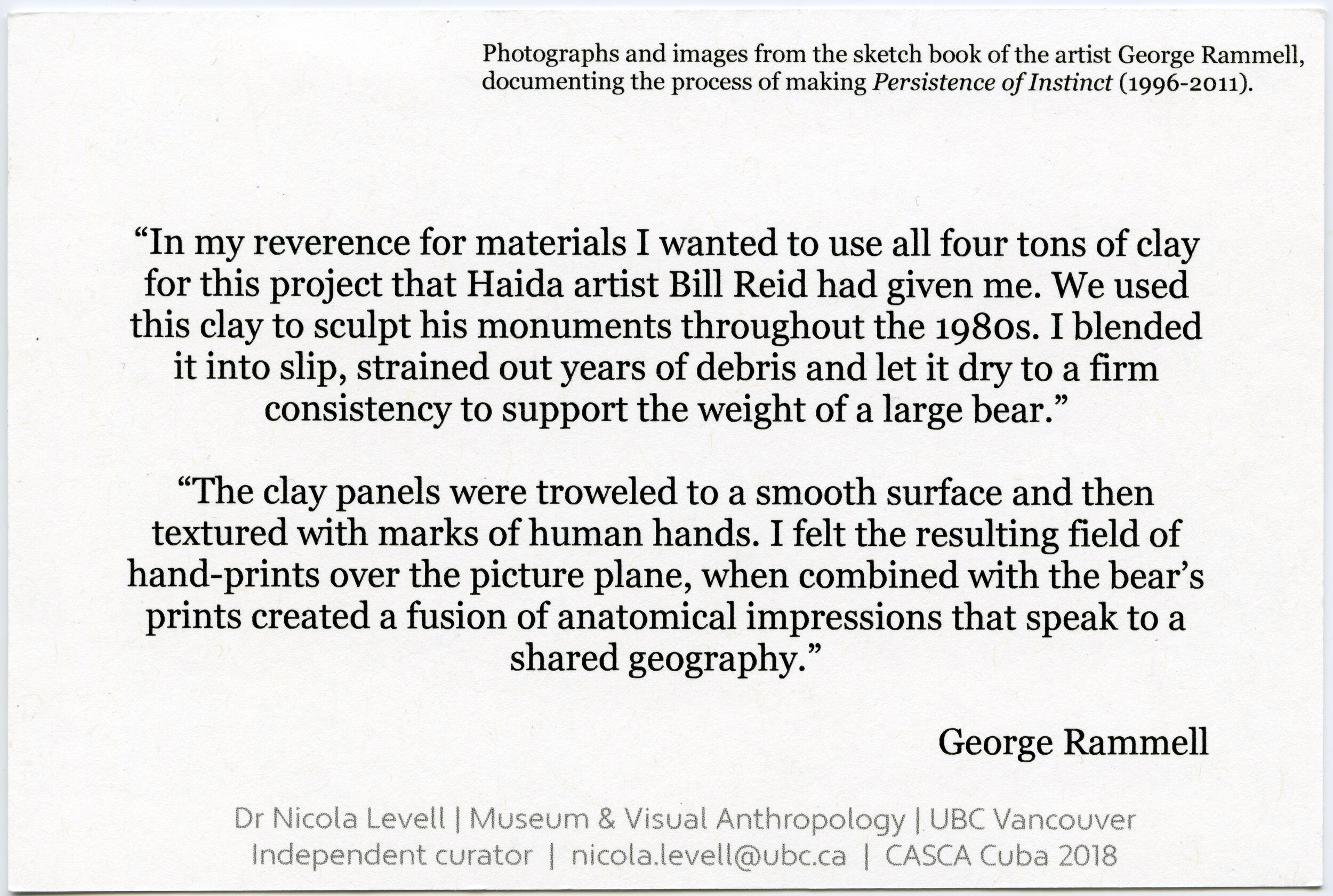

"On the earth" relates directly to the artists' clay and its biography that pulsates, radiates, and connects to the other elements and beings, as Rammell elucidates in his sketchbook notes:

Notably, this huge body of clay had been used in the creation of the monumental bronze-cast sculpture, The Spirit of Haida Gwaii, The Black Canoe (1986), by Bill Reid, which is displayed outside the Canadian Embassy in Washington, DC. Another iteration, The Spirit of Haida Gwaii: The Jade Canoe (1994), is located at Vancouver's international airport, while the full-size plaster maquette can be found at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec. The biography of the four tons of clay is implicated in the bodies and lives of these other artistic forms, their materials and makers, as well as other relations and beings that become entangled as their lives intersect and radiate beyond. Thus, the clay also bears witness to The Spirit of Haida Gwaii being mobilized as a piece of protest art (Bringhurst 1991). In the midst of the federal government's commission, Reid stopped and refused to continue working on the high-profile sculpture. This was an act of defiance and resistance to demonstrate his allegiance with the protesters—Haida and non-Haida, women, men, elders, youth, and others—who had taken a stand against the clear-cut logging on Athlii Gwaii (Lyell Island) in southern Haida Gwaii. For almost two years, the protesters formed a blockade across a logging road; day after day, they were arrested, jailed, and released, only to rejoin the protest line. With support from various sources, including Reid's "tools-down protest," they won their cause (Collison 2018; Levell 2016). At stake was not only the indiscriminate and irresponsible decimation of Haida Gwaii's unique natural heritage but also the pressing issue of an Indigenous people's sovereignty and self-determination, their title and rights to land.

Using the same clay, Rammell's artwork and art practice are likewise a form of protest art. His art is always political in intent, rallying against the resource extractive industries and individuals who are exploiting and raping the environment. On March 22, 2018, Rammell was arrested for protesting on Burnaby Mountain, BC, against the TransCanada pipeline project. In 2018 alone, he created a number of large scale artworks that were carried on protest marches, including satirical puppets and illustrated placards depicting Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau in bed with Kinder Morgan and Rachel Notley, the then premier of Alberta who pushed the pipeline-expansion plan, as a massive shiny, knotted, black-pipe sculpture.

The Persistence of Instinct is similarly underpinned by a strong ethical commitment to the delicate ecosystems, the rainforest, and multispecies interdependency of BC. These interdependencies or connections are indexed in the artwork's iconography.

The "marks of human hands" and "handprints" Rammell refers to are the finger marks of the independent filmmaker Ann Marie Fleming, who was present in Sequim, Washington, when the bear-as-artist walked across the bed of clay. The bear's and the filmmaker's prints are rendered visible through what Rammell's terms "the characteristics of clay as a recording device."

Let's briefly dwell on that idea: clay, and by extension the earth (and potentially all other media), possesses a complex biographical imprint, a memory of the elements and forces, the sentient beings and acts that have come into contact and interacted with it. The biographies (visible and unseen) crisscross, radiate, and multiply through the prism of the artwork and, in this case, the medium of clay.

The origin of Persistence of Instinct is grounded in Rammell's activism and his championing of ursos arctos horribilis, the grizzly bear. Impressed by the intelligent and social nature of grizzlies, the artist worked with several groups in BC to create a grizzly bear sanctuary and ban the grizzly trophy hunt.[1]

On the earth, on the clay connects the bear, the artist, and others to a rhizomatic network of interdependent relations and ecologies: the Persistence of Instinct plays with the relationship of wood or rather trees to the earth and to the forest ecology.

Pink Floyd's Dark Side of the Moon album comes to mind: autobiographical memories of the album cover, of vinyl, of a sound, of a track, of a time, of a feeling—"And all you touch and all you see, Is all your life will ever be," etc. etc. Dark Side of the Moon (1973), close your eyes, imagine, the image of white light passing through a triangular prism to form the bright colors of the spectrum against a stunning black field. According to the blogger David Deal (2017), this image invites listeners to explore the music inside, including Waters's lyrics of alienation, loss, and materialism. So, we end with an example of a radiating auto-associative biography, generated as the light hits the angle of a prism. Some biographies are visible, perceptible, that is to say, they can be sensed: multisensory perception—seeing, smelling, hearing, tasting, touching, feeling, experiencing, embodying—comes into play. Countless other biographies remain unseen by others, unheard, untasted, untouched, unfelt, un . . . yet still they radiate and travel leaving impressions and marks. Although they may be invisible to others, the tenuous persistence of biography is a universal truth: everything in the world, the universe has a life story that interconnects and radiates.

Acknowledgments. I would like to thank the following radiant individuals who in different ways inspired and illuminated this project: Leslie Robertson, Denielle Elliott, Dara Culhane, Mascha Gugganig, Katie Ferrante, Alissa Cherry, and Anthony, Marcel, Felix, and Lucien Shelton. Special thanks to George Rammell, whose generosity, creativity, and enthusiasm are like shards of light that have permeated and excited my research.

REFERENCES CITED

Bachelard, Gaston. 1971. The Poetics of Reverie. Boston: Beacon Press.

Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Boudreault-Fournier, Alexandrine, and Yamile Haber Guerra. 2017. Email sent to CASCA-Cuba Conference participants, August 19.

Braidotti, Rosa. 2006. "Posthuman, All Too Human: Towards a New Process Ontology." Theory, Culture Society 23 (7-8): 197-208.

Bringhurst, Robert. 1991. The Black Canoe: Bill Reid and The Spirit of Haida Gwaii. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre.

Collison, Jisgang Nika, ed. 2018. Athlii Gwaii: Upholding Haida Law on Lyell Island. Vancouver: Locarno Press.

Deal, David. 2017. "The Dark Side of the Moon: How an Album Cover Became an Icon." Medium website, November 26.

Derrida, Jacques. 1987. The Postcard: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gugganig, Mascha, and Sophie Schor. 2020. "Multimodal Ethnography in/of/as Postcards." American Anthropologist 122 (3). https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13435.

Keats, John. 1994. "Lamia." In John Keats, edited by Elizabeth Cook. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kopytoff, Igor. 1986. "The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process." In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 64-91. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levell, Nicola. 2016. The Seriousness of Play: Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas. London: Black Dog Publishing.

Levell, Nicola. 2013. "Beyond Tradition, More Than Contemporary: Four Northwest Coast Artists and Citizens Plus." In Urban Thunderbirds: Ravens in a Material World, edited by Nicole Stanbridge, 38-49. Victoria: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

Parsipur, Shahrnush. 2011. Women without Men: A Novel of Modern Iran. New York: Feminist Press, City University New York.

Taussig, Michael. 2006. "What Color Is the Sacred?" Critical Inquiry 33 (1): 28-51.

Wohlleben, Peter. 2016. The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate. Vancouver: David Susuki Institute/Greystone Books.

NOTES

[1] In BC, the grizzly bear hunt ban came into effect in November 2017.