On the Migrant Image and the Violence of Photography

By Laurence Cuelenaere

I take the term migrant image to convey both the image of a migrant and the image as migrating, as undergoing sematic and semiotic transformations by means of interventions on the original photographs. Migrant images proliferate in both damning and empathetic contexts wherein one same image might lead to a projection of hatred that validates the state violence projected on migrating people or lead viewers to participate in the denunciation of said violence. In this sense, I argue that migrant images at once claim transparency and reveal transparency as an effect.

I define my interventions on migrant images that I have shot over several years as photographic sculptures (when I stitch or veil) and photomontages (when I compose using other photographs). The photographic interventions depicted in this essay seek to interrupt projections of hatred or political validations for migrants’ conditions of impossibility by creating a perceptual caesura that seeks to suspend the taken-for-granted sensibility that migrant images offer an unmediated transparency. My method and approach draw from recent anthropological interventions on the photographic image that recognize and seek to disrupt viewers’ affective attachments to transparency (Dattatreyan and Guillamon 2021; Welcome and Thomas 2021). In the images I share in this essay, I show how the effects of transparency do not refer to capturing an external object/sitter but rather refer to what results from separating the representation from the referent, thereby exposing photography as an anachronistic, yet faithful, practice mirroring life. My interventions, then, question the realistic expectations of the viewer: their demand for an unmediated truth about migration and those on the move.

In The Migrant Image, T. J. Demos (2013) exposes the assumed transparency of global systems of images by elaborating a contrast with the material realities of people confined by a border and the inequalities of social mobility. Building on Eduard Glissant, Demos theorizes “opacity as the reverse of transparency by an obscurity that frustrates knowledge and assigns to the represented a source unknowability” (145). In so doing, he sets up an opposition between opacity and transparency. At stake here are tactics of not complying with demands for normative visibility and legibility (Dattatreyan and Marrero-Guillamón 2021, 276).

My photographic interventions proceed from the claim that transparency (as opposed to opacity) is an effect on the viewer, not a given. Stillness, indispensable for transparency’s claim to truth, is at once disrupted and relocated by interventions that open the image to semantic and semiotic instability. The still photograph, rather than being a mere product of a camera, implies our entire living and emotional self. Its stillness relates to our imagined futures but also to the intensification of life in precarious spaces (including our own). Stillness, from an ethnographic perspective, evokes unique lingering memories, immanent experiences, and affects. Defined as such, stillness implies its opposite; it becomes a multivalent term referring to a nonhierarchical, diachronic site of ambiguity. Photography, in this respect, has become part of our affective complex surrounding the showing, viewing, and freezing of temporality (of suffering). Rather than spatiotemporal points of reference, photography has intensive coordinates.

I locate my photo-ethnography of people on the move (from Cuba, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, Venezuela, Eritrea, Haiti, Honduras, San Salvador, Mexico, and Guatemala, among other places) in Tapachula and Hidalgo, at the border between Mexico and Guatemala, separated by the Suchiate River, and in Reynosa, at the US-Mexico border, marked by the Rio Grande. My photographs are heterogenous, engaging with a range of forms, relationalities, and affects—policing, close-ups of faces, makeshift camps, shelters, intergenerational migrants, juxtapositions of discordant elements, the boredom of wait—that taken on their own would suggest a transparent documentation of migrant life.

I use stitches, veils, photomontages, and fortuitous juxtapositions of objects/sitters to function as an affective barrier between the viewer and the sitter in the photograph. I intend, by deploying these techniques, to curtail reifications of victimhood (or for that matter of my own precarity in a “conflict zone”). As such, I take the risk of degrading, of destroying the “quality” of my photographs, to interrupt their presupposed transparency. This sort of degradation challenges the epistemological register of ethnographic representation grounded on a referential certainty (or transparency).

As in the case of the migrant image, the idea of photographing violence implies a dual sense of photography as documenting violence and as exercising violence by the act of photographing itself. This dual sense has an obscure underside that connects photography to the history of colonialism. The photographer’s gaze does not only participate in the production of the photograph itself but also in the transformation of that which it records. The objects/sitters cannot be freed from the logic of violence that once objectified them. There is a certain inevitability in photography that needs to be countered to break the spell of transparency. Consider the Ecuadorian migrant forced to wear an ankle bracelet, a form of imprisonment, which I have inserted into a page from a Mesoamerican codex to accentuate her belonging to Abya Yala (a term used by Indigenous people for the continent usurped as America).

Lowell, Massachusetts, 2022, Inkjet Print, Slide.

Representations of violence reproduce the same logic they seek to disrupt. Visual and written representations involve the conscious or unconscious framings (aesthetic, historical, moral, legal) that reproduce violence on an epistemic, structural, and symbolic level (Rabasa 2000). They exhibit how power and terror get displayed in “spectacles” of historical events. In their representation, they reiterate the compelling force that power uses to establish its authority. As such, even well-intentioned photography often provides fodder for the projection of hatred and the celebration of violent scenes.

The question, then, is how can we take a conceptual stance to violence without replicating it, especially if we consider that violence may also be found in being marked migrant, Black, Indigenous, or (il)legal through the white “debilitating fantasies of race” (Campany and Wolukau-Wanambwa 2022, 43)? What matters, I think, is who gets to inhabit and be part of these (debilitating white) fantasies of race and integrity. If I am singling out the migrant with my lens, I also underscore the power of fragmentation and fractures through my interventions on the image.

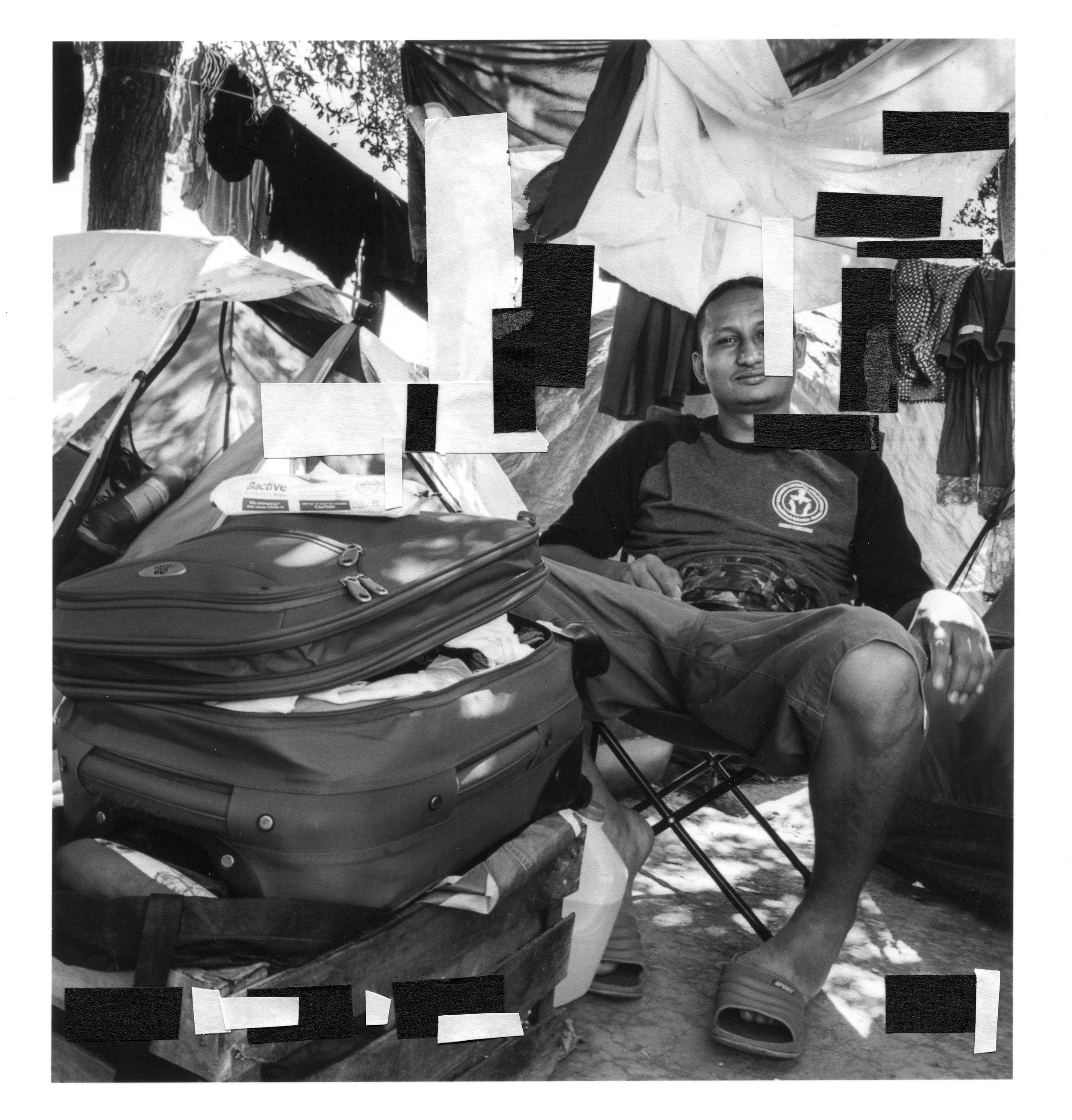

Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico, 2021, Inkjet Print, Tape.

Lounging on a chair, the man depicted embodies the boredom of waiting for months, if not years, for an interview. His foot resting outside his sandal and his bursting suitcase underscore the lethargy induced by an uncertain future in which all there is left to do is wait. I have placed strips of paper to try and lead viewers out of a comfortable reading of the image as merely depicting the restfulness of migrants and their resources, as if the violence that led to his escape from the horrors of El Salvador were a mere fiction.

The Guatemalan sitter holding a cell phone in a camp at the border in Reynosa also manifests the precarity of living in a camp, but the photograph also illustrates the juxtaposition of reality and the representation of it: she is in the encampment without electricity holding the phone that informed us that there was no electricity. By placing the phone between herself and my camera, she gives her narration a surreal twist; reality and its representation coalesce in their juxtaposition. She knows the power of the screen.

Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico, 2021.

Whereas veils and stitches fragment and recompose the relationship between viewer and photograph, they also mediate the viewer with the spectrum of the image warding off powers that seek to destroy life. Stitching and veiling emphasize wounds manifest in the bodies recorded by the camera that could otherwise go unperceived or reduced to transparent truths. They open the photograph to multiple understandings.

Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico, 2020, Inkjet Print, Veil.

The veil over the close-up of a Haitian asylum seeker prompts questions regarding the crisis that led him to leave Haiti. It disrupts that apparent tranquility of sitting in a park in Tapachula (also named “prison city”) in wait for a visa to travel to the northern border with the United States.

Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico, 2021, Inkjet Print, Stitches.

The stitches foregrounding the image of a Honduran mother holding a baby situate their location in a street bustling with traffic, people crossing the street. Mother and baby are one component in a cityscape of poverty that undoes their victimhood specific to migrants stuck in Tapachula.

Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico, Juxtaposed Inkjet Prints.

The insertion of images of wealth surrounding a Guatemalan grandmother holding a baby talking on a cell phone (to her father, I learned, still in Guatemala) creates a photomontage that questions the transparency of the photograph rather than the reality of a fragmented world. It is and is not a mere image of a grandmother and child.

By means of photomontages, stitches, veils, and juxtapositions of objects/sitters, I have interrupted the transparency of the image. It is not simply about rendering photographs opaque—that is, signaling the impossibility of capturing truth, as Demos has argued. Rather, it is about opening the image to multiple readings that may have the effect of transparency as a point of departure. I have defined my interventions as photographic sculptures and photomontages. In both cases, I motivate the photographs as an allegoresis: they say this and mean that.

Acknowledgments

Many migrants expressed hope that I would bring their stories beyond their immediate situation; they made this work possible, and I thank each one of them for giving me permission to photograph them. Also, many thanks to the editors of American Anthropologist for their caring editorial advice, in particular to Gabriel Dattatreyan.

References Cited

Campany, David, and Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa. 2022. Indeterminacy: Thoughts on Time, the Image, and Race(ism). London: MACK.

Dattatreyan, Gabriel, and Isaac Marrero-Guillamón. 2021. “Pedagogies of the Sense: Multimodal Strategies for Unsettling Visual Anthropology.” Visual Anthropology Review 37 (2): 217–476.

Demos, T. J. 2013. The Migrant Image: The Art of Politics of Documentary during Global Crisis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Rabasa, José. 2000. Writing Violence on the Northern Frontier. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Welcome, Leniqueca, and Deborah Thomas. 2021. “Abstraction, Witnessing, and Repair; or, How Multimodal Research Can Destabilize the Coloniality of the Gaze.” Multimodality & Society 1 (3): 391–406.

Cite As

Cuelenaere, Laurence 2023. “On the Migrant Image and the Violence of Photography.” American Anthropologist website, May 18.