Figuring Ethnographic Fiction

By Noah Amir Arjomand (Indiana University)

Figure 1. In a monochrome drawing of Gezi Park, Istanbul, a young woman with flowing hair and a scarf around her neck translates between a group of protesters holding an “Anti-Kapitalist Müslümanlar” banner, and a young male reporter holding a notepad and wearing a camera around his neck. Behind them, other protesters congregate around a bus. Farther in the background, demonstrators have draped a building with a variety of antigovernment signs.

My book Fixing Stories: Local Newsmaking and International Media in Turkey and Syria centers the figure of the news fixer. In journo lingo, a fixer is a local guide and interpreter who opens doors for foreign reporters and helps them make sense of the information they collect—journalism’s version of ethnography’s research assistants and key informants. Fixers mediate between the expectations of their clients and those of news sources, brokering fragile unities among disparate interests and choreographing working misunderstandings that allow news to get made. Between 2014 and 2016, I interviewed and observed reporters and fixers; I also worked in both roles myself (as seen on the right below, struggling to consecutively interpret an interview over tea).

Figure 2. In this drawing, a bearded man in his late twenties with dark hair who resembles the author acts as an interpreter between a middle-aged male journalist and a female source in her thirties. The interpreter looks confused and gesticulates with both hands. The three sit in chairs in an apartment around a low table on which rest glasses of tea and small plates of snacks.

To tell the stories of the career paths of fixers I encountered and about my own experiences as a reporter and fixer, I created a collection of composite character narratives. I did so first and foremost to protect research participants’ anonymity. Journalists produce public work that their colleagues monitor, and if I had simply changed names, it would be easy for insiders to unmask my characters. There was a real risk of reputational harm for people who had shared their secrets and criticism with me. Relations among reporters, fixers, and sources are fraught with mistrustful and tentative reciprocities, and journalism is a game in which, as the late Janet Malcolm put it, “If everybody put his cards on the table, the game would be over.” Media workers have also been imprisoned in Turkey and killed in Syria at appalling rates in recent years. I worried about adding to the risks my interlocutors already faced from violent state and nonstate groups.

In assembling multiple real-life interlocutors into each fictional character, I created a hybrid fiction grounded in real evidence. I devised a method of fictionalization, which I detail in an appendix, meant to hold me accountable to evidence that might surprise me and disrupt my assumptions while also making my creative hand as storyteller clear to readers. The resulting composite characters were not purely the products of my imagination, nor were they representations of abstract ideal types dressed up in people clothes. I aimed to create characters that were true, in the sense of being objectively possible, but who did not exist in the real world.

I am a documentary photographer and filmmaker and so had some sense already of how to communicate ideas and tell stories through two-dimensional imagery. To visualize these true-but-not-real narratives, though, I was drawn to illustration over more familiar media forms precisely because it lacks the indexical “realness” of photography.

My starting point was cartoonist-journalist Joe Sacco’s brilliant book The Fixer: A Story from Sarajevo. Joe was kind enough (with the intercession of a fixer of sorts—our mutual friend, journalist Naresh Fernandes) to allow me to use a panel from his comic for the cover of Fixing Stories, one which wonderfully captures the ambiguity of source-fixer-reporter interactions. Why does the man in the center want to talk to Joe? What does the fixer on the left expect in return for the “treat” of translation?

Figure 3. The book cover features a panel from a black-and-white comic depicting three men. A fixer smoking a cigarette tells a foreign reporter sitting across from him, “This man wants to talk to you. I will translate. As a treat.” The fixer refers to a man with a troubled face who stands beside them.

Once the cover art had whetted my appetite, I decided I also needed illustrations within the book. I had already created some abstract diagrams to capture ethnographic constructs of another kind: the general relational patterns, ideal types, and concepts that I used in formal theoretical discussions and to draw comparisons among characters. In the diagram below, for example, I visualize sources, fixers, reporters, and editors as constituting links in a chain of brokers that stretches from events on the ground to news on the page or screen. I show how depending on their position along that chain, actors are afforded either more information control (over who knows what and accesses which people and places) or more frame control (over what information is deemed newsworthy and in what context)—key concepts for understanding how news gets made.

Figure 4. This diagram titled “The Chain of News Production – abbreviated” features a chain of four links stretching from left to right, with links respectively labeled “source,” “fixer,” “reporter,” and “editor.” Underneath the chain is a horizontal bidirectional arrow, indicating a spectrum along which links of the chain fall. On the left (“source”) side, the arrow points to “information control.” On the right (“editor”) side, the arrow points to “frame control.”

But I also wanted images to accompany the narrative sections of my book that would help readers to imagine the lived experiences of news fixers. With help from Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, a correspondent for The Guardian and talented artist in his own right, I found Tora Aghabayova to visualize my composite characters. An Azerbaijani multimedia artist living in Germany, Tora had illustrated many news stories for journalists and spent a good deal of time in Turkey, so she knew both the people and the place of my book.

Tora’s portfolio includes sumptuous oil-on-canvas paintings and eye-catchingly colorful editorial work. The black-and-white sketchy look of the drawings I commissioned was both a practical choice (Cambridge University Press had not budgeted for color images) and a purposeful one. Whereas a symbolic diagram is the visual equivalent of typology, a naturalistic sketch of protagonists in action is a fitting companion to possible but unreal composite fiction.

Just as I hoped to self-consciously undermine my own authority as chronicler and expert by explicitly labeling my text as fiction, I hoped that Tora’s drawings could bring my writing to life without the implicit true-story claim to authority of a documentary photograph. The rough edges and cross-hatched shading of her sketches left the creative hand of the artist very much visible.

Tora was able to capture the characteristic gestures of actors playing various roles in newsmaking, emplace those actors in the settings where their actions made sense, and make their social positions visible through their physical positioning in the frame. The following passage about a fixer-reporter team in the southeastern city of Diyarbakır, for example, is accompanied by the image below it.

Geert, the Belgian reporter, who found Nur through the foreign press club’s fixer list, recalled working with her on a story about political conflict within the Kurdish community. Among others, he wanted to talk with representatives of The Free Cause Party, the political wing of Kurdish Hizbullah known by the abbreviation Hüda-Par (which like Hizbullah means “The Party of God”). Sunni Islamist Hizbullah members had murdered numerous journalists and, Nur believed, her brother’s high school teacher. They also threw acid on the faces of women or strangled them for failing to observe Islamic modesty.

She called up a Hüda-Par politician whom she had cultivated as a source. Nur—a woman wearing a leather jacket and no headscarf in a meeting room with Geert and a group of men who thought the proper place for a woman was in the home—acted nothing but polite.

Nur waited until they were in a taxi after the interview, Geert later recollected to me with a chuckle, to explode with counterarguments and refutations of all the lies she said the Hüda-Par representatives had told. Her activist, leftist, feminist self was not gone, just checked at the interview door for her performance of neutrality.

Figure 5. In this drawing, three late-middle-aged men sit in armchairs in front of a Hüda-Par flag. Opposite them sit a young woman fixer with short dark hair wearing a leather jacket and pants and a fair-haired man holding an audio recorder in his right hand and using his left hand to hold a pen and balance a notebook on his left knee.

Tora’s image brings this passage to life. Nur sits between Geert and their sources, her hands tensely but politely resting on her knees and her body inclined forward in a posture that could be deferential or defiant. Two of the Hüda-Par politicians stare at Nur, but the speaker in the center looks past her to address Geert, disregarding Nur as a non-person serving a mechanical function as translator.

Tora could also help to situate my characters in distinctive times and places. Answers to the questions of who becomes a fixer, how they fix, what they use fixing to achieve, and what dangers they face always depend on circumstances. Reporting the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul (see the first image below the article’s title) required different skills than reporting ISIS’s siege of Kobani from the Turkish-Syria border (below) and involved different assemblages of news contributors. Different kinds of people acted as fixers in the rush to cover Gezi than in the long, evolving struggle to cover Syria’s civil war. I provided Tora with reference photos, both my own and those I found from other sources, and we discussed the social geography and salient physical features of these historical moments at length as we went back and forth with design ideas and then rough drafts.

Figure 6. A drawing: some dozen journalists and onlookers stand on a barren hill overlooking the city of Kobani, from which multiple plumes of smoke rise. Some of the journalists are filming the city, including one team with a correspondent holding a microphone who addresses a tripod-mounted camera with Kobani behind her. Midway between the people in the foreground and the city, a line of Turkish tanks is parked along the Turkey-Syria border.

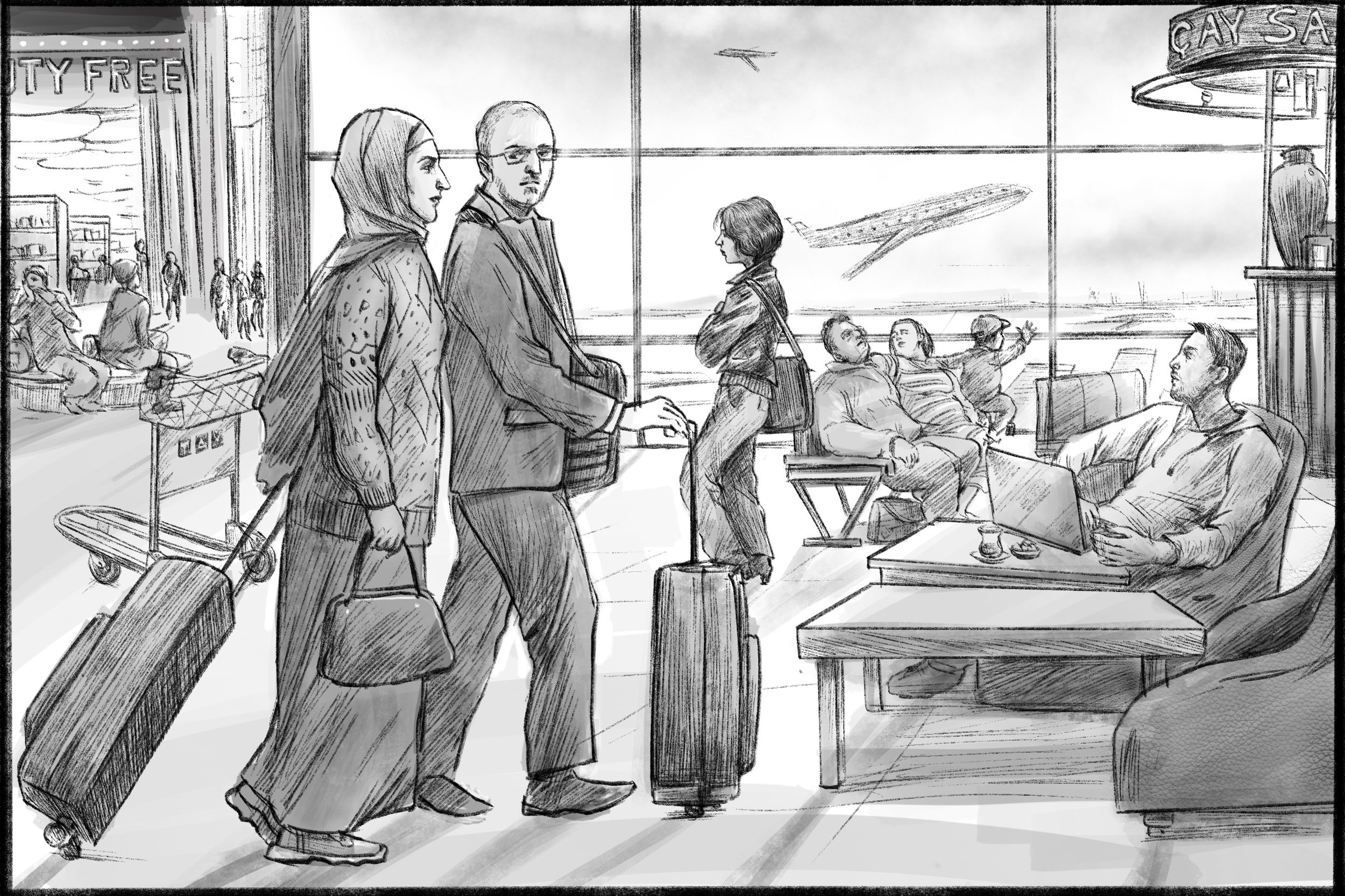

By way of conclusion: whether an ethnographer creates composite characters, their writing likely selects, compresses, and remixes participants’ experiences and speech for both analytical and literary reasons. Drawings, as compared to photographs or video, can be handy companions to such texts because they can visually realize this imagined juxtaposition and recombination of diverse figures (as below, where four of my protagonists cross paths at Istanbul airport, each on their own career trajectory) while also underlining the constructedness of the author’s narratives.

Figure 7. This drawing shows several people walking through Istanbul’s airport with duty free and tea shops in the background. Among the people we see the reporter pictured in Figure 1 sitting in an armchair using a laptop and the fixer from Figure 5 walking. Most prominent in the foreground are a man and woman with rolling luggage and handbags. He has thinning hair and wears spectacles and a blazer; she wears a headscarf, sweater, and floor-length skirt.

CITE AS

Arjomand, Noah Amir. 2022. “Figuring Ethnographic Fiction.” American Anthropologist website, March 19. www.americananthropologist.org/online-content/figuring-ethnographic-fiction.