Completing the Journey: A Graphic Narrative about NAGPRA and Repatriation

By Sonya Atalay and Jen Shannon

NAGPRA AND THE 10.11 REGULATIONS

This comic explains in plain terms what NAGPRA is, why it was enacted, and how what are legally termed “culturally unidentifiable individuals” and “associated funerary objects” are treated under the law. We reference the law itself throughout the comic (for example, see page 5 of Journeys to Complete the Work).

NAGPRA empowers tribes to request the return of human remains, funerary items, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony from museums and other institutions. Our purpose in selecting the topic of this first NAGPRA Comics issue was to expose a fundamental inequality that the new NAGPRA regulations, shorthanded 10.11, introduced under the law: for those individuals who are determined to be affiliated with a particular cultural group, the law mandates that their associated funerary items be repatriated with them, but for “culturally unidentifiable” individuals, or individuals classified as without cultural affiliation, their associated funerary objects are not required to be returned.

Originally, the procedure to repatriate “culturally unidentifiable” individuals was not included in the law. To do so, a museum had to consult with many tribes and determine an appropriate course of action, then bring the case for review before the National NAGPRA Review Committee. For example, the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History consulted more than eighty tribes on a single case, presented it to the committee, and then returned the funerary items with the individuals—keeping in line with the mandate for culturally identified individuals—to one tribe who agreed to take the lead. When the 10.11 regulations were released in 2010, they were helpful in that they streamlined the process, but they did not require that culturally unidentified ancestors and their traveling items remain together.

COLLABORATION, CULTURALLY SENSITIVITY, AND THE GENRE

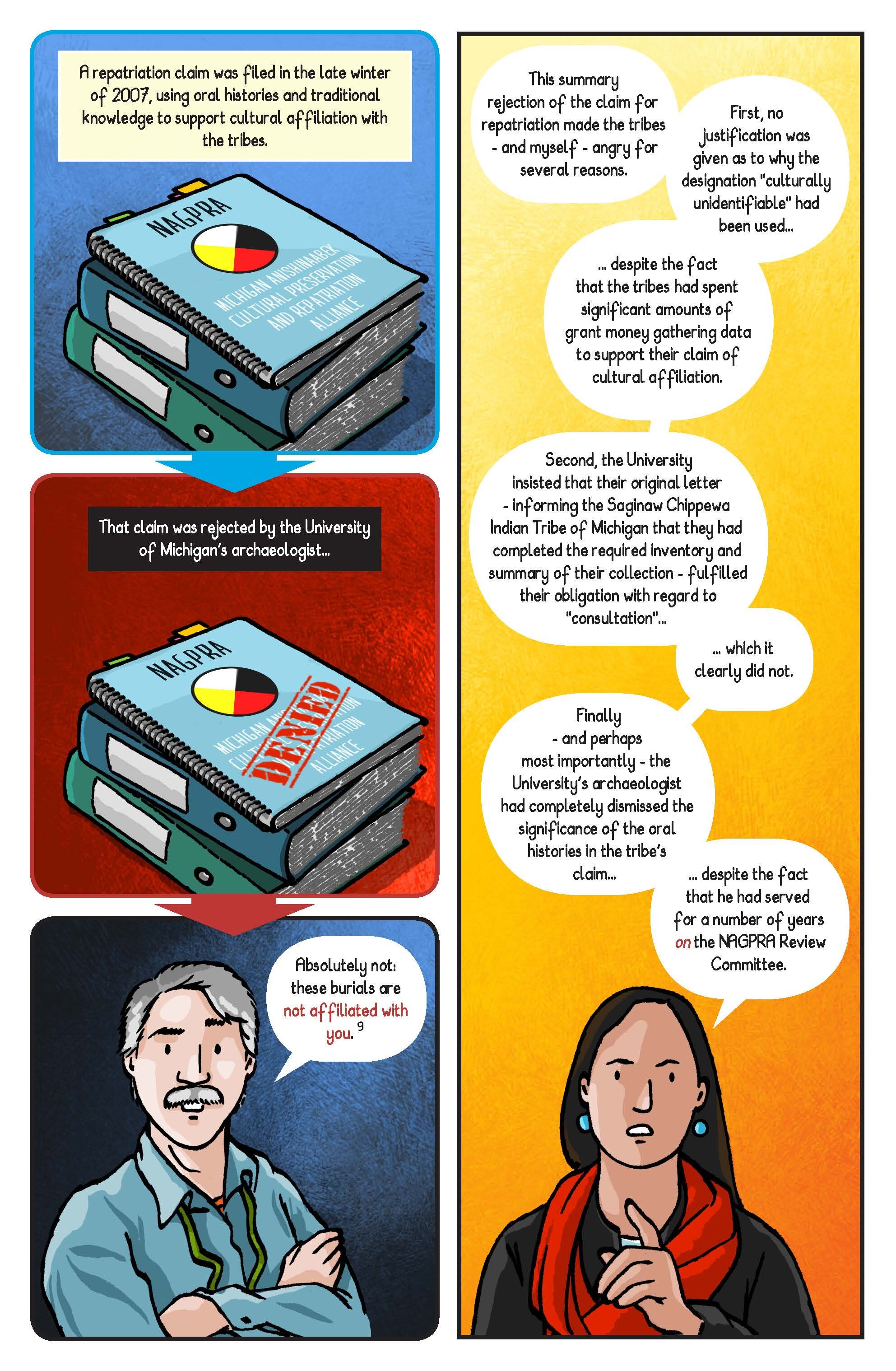

NAGPRA Comics is produced collaboratively with Native communities and seeks to highlight their perspectives and experiences regarding the implementation of the law. Journeys to Complete the Work provides two case studies relating to the 10.11 regulations. In the first story, involving the University of Michigan, community activism and dialogue with museum officials resulted in the return of Native ancestors (human remains) and their traveling items. The University of Michigan is now a leader in repatriation policy. In the second case, Harvard did not return the traveling items with the individuals. We show the community’s response and how they studied the museum’s collection to create new traveling items to accompany these individuals in the recommitment, or reburial, ceremony.

This project was always about the NAGPRA regulations, but it did not start out as a comic. Our first idea was a white paper, then an animation, perhaps an animated storyboard. Working collaboratively means being open to unanticipated directions and taking time to build relationships and trust. It means being open to failure and that research partners have the ability to say no. Our first attempt to tell a NAGPRA narrative was rejected; it was a good learning experience for us about the perception of the genre and how to structure future collaborations.

The first NAGPRA case study we drafted was a story based on our experience witnessing a national NAGPRA meeting and transcripts of the hearing posted at the national NAGPRA website. It did not matter if it was in the public record; we still wanted community participation to move forward. Our draft was reviewed by the tribe’s research review board and they declined to work with us on it. At the heart of the matter was the genre of comic books itself: they were concerned that it would be a disrespectful manner in which to address issues of sacred items and traditional knowledge, and that their knowledge could be seen as fictional if depicted in this medium. These are important and serious concerns about the implications and consequences of the genre.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

These concerns made us think deeply about how, in this particular medium, we communicate respect and sincerity in our treatment of culturally sensitive subject matter. Language matters, as do the aesthetics and design. These concerns affected the choices we made about what to include and exclude in the telling of these stories. The aim was to convey true stories respectfully and in a way that makes them accessible. Keeping this in mind, John, the comic artist, used sequential panels that highlighted individuals’ voices and their different perspectives. The panels helped establish a clear progression through time. And citations signaled research and accuracy.

Our process was iterative and based on “face-to-face” dialogue—some in person, much of it via Skype. Sonya provided appropriate photographs to inform John’s artwork, being mindful of representing the recommitment ceremony without indicating its location. John did online research for people’s images and quotations. Jen provided research on the law and the museum perspective. Once John produced a draft with sketches and text, it was provided to Shannon Martin (Gun Lake Pottawatomi and Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe) and her colleagues at Ziibiwing Center for Anishinabe Culture & Lifeways for review. They did multiple rounds of edits, which we incorporated into the final book.

Unlike an academic paper, the comic required us to make decisions about how to depict people, action, and content, and what colors to use in doing so. The look of the comic that John developed was intended to communicate vibrancy and agency. But colors are “read” just as words are. Shannon Martin and Sonya “read” some of the early drawings as Haudenosaunee because of John’s color choices. The selection of colors was changed to those with distinct meaning for Midewiwin people, making them gender and clan appropriate to Anishinabe people. People “read” and understand the comic differently depending on the Midewiwin knowledge they carry. The iterative editing process, and embedded layers of cultural interpretation, resulted in the leadership at Ziibiwing feeling it was their story and that it was appropriately told, and they have distributed it widely.

CONCLUSION

Repatriation facilitates healing and well-being, for both Native communities and for the museum professionals and archaeologists involved in handling these ancestors (Atalay 2019; Shannon 2019). So does providing media through which people can communicate their own perspectives on the repatriation process. We see this comic book as an extension of community activism regarding NAGPRA—on behalf of Native communities and museum professionals. And we are encouraged that Native community members, archaeologists, and educators have requested copies.

NAGPRA Comics highlights that repatriation builds relationships and makes further research collaborations possible, often resulting in new, exciting, and cutting-edge projects. For example, after the University of Michigan repatriation described in the comic, the university’s Matthaei Botanical Gardens and Nichols Arboretum, and the Museum of Anthropological Archaeology worked to collaboratively study seeds in a collection at the university and developed a sustainable foodways project. At the University of Colorado, repatriation of sacred objects led to a museum/community partnership that produced a community-driven oral history video documentary and a community-based video workshop series.

There is still much work to be done under NAGPRA so that all the ancestors can make the journey home and complete their work of giving back to the earth. We have several community collaborations underway to continue our work with NAGPRA Comics to help people understand these important journeys, and plan to release additional comics in the series later this year. The digital versions can be accessed and downloaded online.

REFERENCES CITED

Atalay, Sonya. 2019. “Braiding Strands of Wellness: How Repatriation Contributes to Healing through Embodied Practice and Storywork.” The Public Historian 41 (1): 78–89.

Shannon, Jen. 2019. “Posterity is Now.” Museum Anthropology 42 (1): 5–13.